{{item.title}}

{{item.text}}

{{item.text}}

We have pulled the results into five separate summaries covering the key takeaways from the latest data. Part One: Economic crime is increasing, but are you surprised? provides a summary of the main survey results and shares the top level insights. Part Two: Fraud in a Pandemic: What do the numbers tell us and should we be concerned? examines the effect of COVID-19 on fraud and the changes organisations experienced as a result of the pandemic. In this third summary, we focus on the types of perpetrators that are the most disruptive for businesses and the potential financial impact of this disruption.

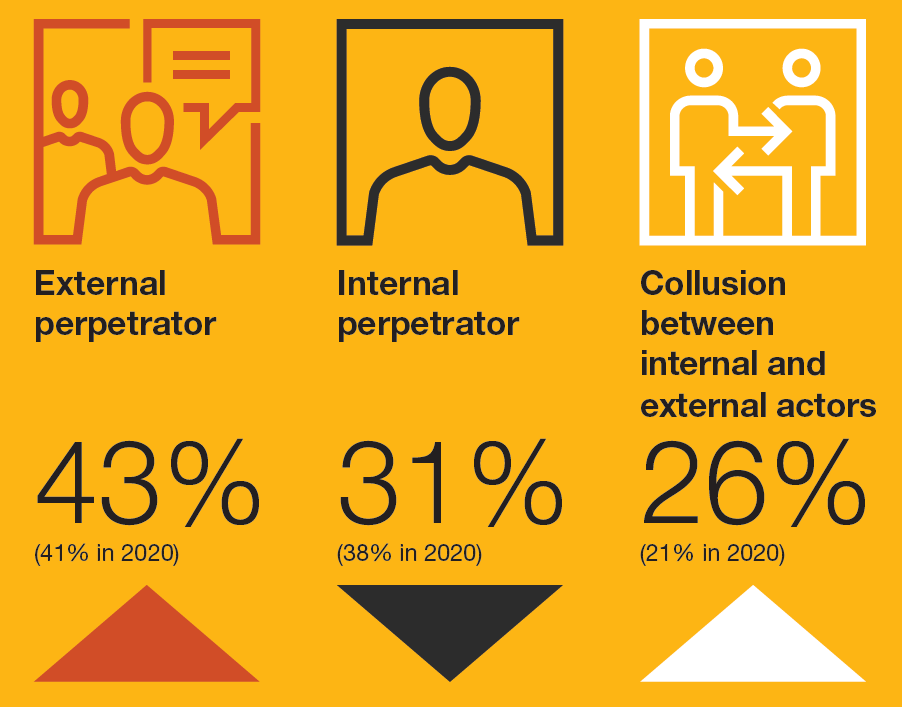

43% of global respondents reported that external perpetrators were mainly responsible for the most disruptive or serious fraud experienced.

External perpetrators continue to be the main perpetrators of fraud, with an increase of 2% from the last survey. Reports of internal fraudsters have decreased significantly, mainly due to a rise in collusion between internal and external perpetrators.

Main perpetrators of the most disruptive or serious fraud experienced globally

40% of respondents from Asia Pacific (APAC), including New Zealand, reported that the most disruptive fraud they experienced were conducted by people outside of the business, compared to 43% globally. The type of external fraudster also continues to evolve, with the role of hackers and organised crime rings increasing in the last two years to represent over 60% of identified external perpetrators.

As borders continue to open up and global mobility is increasing, the opportunities for transnational and domestic organised crime are also increasing. We observe the growing sophistication and diversity of economic crimes involving organised crime, both here in New Zealand and abroad. Organisations previously considered immune from this threat can be exposed to these actors in novel and unforeseen ways.

Combating external bad actors can be different from containing internal fraud, because organisations have less control over the perpetrators’ actions outside their systems. External actors are also known to collaborate with other external parties, increasing both the volume and sophistication of attacks. This is further facilitated by the increase in anonymity-protecting technology, such as the dark web, cryptocurrency and chat rooms. However, no matter the source of the fraud, effective response remains consistent. You need to know what is happening and quickly. Early detection and systems to prevent bad actors reduce exposure to the risk, and provide a sound basis to respond, when identified.

Over a quarter of global respondents reported that internal and external actors cooperating together were responsible for their most disruptive incident of crime or fraud.

Globally, while external perpetrators are the main perpetrators of crime and fraud, in many instances, there is collusion between both. This collusion can be the source of the most disruptive economic crime events. Business partners remain a risk and economic crime committed by management has been consistent since our 2020 survey. Overall, organisations are increasingly exposed to more diverse and sophisticated groups of perpetrators, including threats from both internal and external individuals. This requires organisations to constantly remain vigilant.

30% of APAC respondents reported that their most disruptive incident of fraud was perpetrated by internal and external individuals working together. It is increasingly important that organisations are aware of their internal controls risks, but also how these risks may be enhanced via external factors.

Middle and senior management are identified by Asia Pacific respondents as main internal perpetrators of fraud and crime.

36% of respondents from the APAC region (compared to 31% globally) reported that the internal fraud they experienced was conducted by someone at a Senior Management level. A further 27% of internal perpetrators held a Middle Management role (compared to 24% globally).

These numbers demonstrate that while external fraudsters are on the rise, organisations are not wholly resilient or exempt from fraud occurring internally. In our experience, this reflects the access that senior employees have to heavily controlled parts of organisations and their knowledge of systems and processes, combined with the potential capacity to override key controls.

17% of global respondents reported losses of between US$100,000 and US$1m over the last 24 months due to incidents of fraud, corruption and other economic crime.

The cost of economic crime extends beyond just the financial losses. For external fraud the impact is more commonly a financial loss for the impacted organisation. In the case of internal fraud, the resulting losses can be more complex. This includes the costs and resources committed to managing and mitigating risks, as well as the negative cultural implications from the significant breach of trust that results from economic crime.

Both internal and external fraud can have additional repercussions such as reputational damage, regulatory fines, or the loss of both current and potential customers. 19% of APAC respondents reported losses of between US$100,000 to US$1m due to financial crime in the last 24 months. This sum alone incorporates the actual loss due to the financial crime, potential regulatory fines, and the potential cost to remediate, however, does not account for any reputational and cultural damage, or loss of business.

An organisation was subject to a phishing incident by an external perpetrator. The external perpetrator was impersonating a verified third party and requested that the bank account number be updated to another bank account they controlled. To do this, the external perpetrator used a malicious email system they controlled to send and receive emails with the client, entirely removing the third party from the email chains. They used an email address that was similar to the actual third party email address so unless someone looked at it closely it would appear to be correct - for example, the actual email address for the third party is @thirdparty.co.nz, however, the external perpetrators used the the address @thirdpartyco.nz.

Approximately NZ$150,000 was paid into the account of the external perpetrator and was only detected when the third party complained that their invoices were not being paid.

The external perpetrator was able to do this because they successfully completed the following steps:

Likely compromised the IT systems of a less secure third party.

Identified existing relationships between the third party and their clients.

Intercepted a legitimate email thread between the third party and their client.

The external perpetrator then used this email thread to pretend to be the third party and request a change in bank account information that the invoices should be paid to.

These first three steps are crucial to what the external perpetrator was trying to achieve. Without successfully completing these they would be able to go onto the fourth step. By compromising the third party and intercepting legitimate email communication they were able to add perceived legitimacy to the request to update the bank account number. The perceived legitimacy meant that the bank account number was updated without verifying the request.

The survey and the case study demonstrates that external perpetrators remain a key concern for businesses both here in New Zealand and globally. Below we provide some key areas to pay attention to to mitigate the risk posed by external perpetrators:

Attention should be paid to the small details in emails. The formatting of the email from the external perpetrator was different from other previous legitimate emails, this should have alerted staff to look further into the request.

Confirm changes in bank account details with the supplier. Don’t respond to the email requesting the update, contact the supplier using a previously provided phone number. Any phone number on any invoices provided with a request to change bank accounts have likely been changed to a number controlled by the external perpetrator.

Take the time to identify where opportunities exist for a fraudster to exploit a product and cause financial, legal, or reputational damage. How could it happen, what would it take to prevent it from happening, and what type of response is needed if it happens?

Protecting customer-facing channels requires a delicate balance between ensuring that users have a great experience and detecting and stopping fraudsters. These don’t need to be competing objectives, maintaining the desired user experience, keeping customers safe, and at the same time keeping false positives as low as possible and catching true fraud can be achieved through a combination of strategy, processes and anti-fraud technology.

Often, fraud signals will come from disparate, disconnected systems and frequently are only detected by accident or through the occasional manual review. It is crucial that fraud indications are orchestrated into a centralised platform that can track the end-to-end life cycle of users (fraudsters or not) and generate meaningful alerts.

Regular check-ins with relevant third parties throughout the year is important to ensure you always have the most up-to-date information about the entities you deal with.

PwC’s Forensic Services team uses global methodology to help clients to build trust and closely manage the risks associated with business fraud, financial crimes and other irregularities. Our Forensics Services team provide the following services:

Forensics Investigations

Digital Forensics & Incident Response (DFIR)

Anti-Money Laundering, Countering Financing of Terrorism, and Sanctions compliance

Forensic Accounting

Fraud Prevention, including maturity and risk assessments

Protected Disclosure and Whistleblower Services

{{item.text}}

{{item.text}}