2023 General Election Tax Policy Update

With the general election date set for 14 October 2023, New Zealand’s political parties have been announcing various tax policy proposals to capture voters' interest and support. Tax, as usual, forms a key part of the various parties’ platforms. From tax cuts to universal basic incomes, and from tax-free thresholds to flat tax rates, this edition of Tax Tips summarises what various parties have shared with the public to date.

There are a range of issues ‘front of mind’ for New Zealanders heading into this election - inflation, cost of living, housing, and climate change are among the top five according to Ipsos latest Issues Monitor published in May this year. As a result, we can see many of the tax policies put forward by New Zealand’s political parties attempting to respond to these issues. Our Tax Tips article considers the various proposals put forward by the parties in these key categories:

If you would like to discuss what the above developments mean for you, please reach out to your usual PwC advisor.

Major parties announce their tax policy

The Labour Party made its first big tax policy announcement on 13 August 2023, headlined by their proposal to remove GST fresh fruit and vegetables (funded in part by a proposal to remove depreciation deductions for commercial buildings). The National Party have now announced their full tax policy package which is headlined by adjustments to personal income tax brackets and other income support for individuals and families, funded by a raft of revenue-raising measures.

Given the current economic and fiscal climate, the focus has been on what the parties are offering to alleviate cost of living pressures, and how the parties intend to fund these promises.

The Labour Party’s proposal to remove GST on fresh fruit and vegetables is only partly funded by corresponding tax increases (i.e. the removal of depreciation for commercial buildings) with the remainder funded by existing budget allowances (i.e. money set aside in the Government’s budget each year to fund new policy initiatives).

The National Party on the other hand have presented their package as being “self-funded”, meaning that every dollar of reduced tax revenue is intended to be matched by cuts to spending or new taxes:

A new 15% “foreign buyer” tax on the purchase of residential properties worth over $2 million;

Removing depreciation deductions for commercial buildings (matching the Labour Party’s proposal);

A new tax on offshore online gambling operators; and

Immigration levies.

PwC view

The National Party’s commitment to “self-fund” its tax policy package has required it to propose a raft of revenue raising proposals which, in our view, would challenge some well established principles of what constitutes good tax policy.

The proposed “foreign buyer” tax on residential properties appears to effectively be a new stamp tax for properties worth over $2 million. Although, as the National Party states, there is some form of stamp tax in the UK and many states/provinces across Australia and Canada, the advice provided by the Treasury and Inland Revenue to the 2018 Tax Working Group recommended against the introduction of stamp taxes, on the basis that they are an inefficient tax. A tax on only a certain class of assets, of a certain value could distort investment decisions and stamp taxes are often associated with high compliance and administration costs. There is also a question as to who bears the incidence of the tax, notwithstanding that it will be paid by the “foreign buyer”, as there is a possibility that the “foreign buyer” would take into account the 15% tax when considering the purchase price which could result in a decrease to the actual purchase price paid.

There is scarce detail in relation to the proposals relating to offshore online gambling operators. We note that offshore online gambling operators are already subject to the remote services GST rules, and offshore sports and racing betting operators are subject to:

Information use charges (IUC), which are paid to sporting and racing industry bodies for the right to offer bets on those sports/racing codes;and

Point of consumption charges (POCC), which are a turnover tax paid in relation to offshore betting operators’ gross betting revenue.

To the extent that offshore online gambling operators without any physical presence in New Zealand do not pay New Zealand income tax, this is no different to any other non-resident business which does not have a physical presence (or “permanent establishment”) in New Zealand. The revenue “gaps” from offshore online gambling operators are likely to be in the form of the 4% casino duty and 0.87% problem gambling levy which are paid by licensed domestic casino operators. However, revenue from the problem gambling levy is hypothecated (i.e. ring-fenced) specifically for spending on public health and other harm minimisation programmes and is not used to fund general government spending (e.g. on general tax cuts).

Labour’s proposal to remove depreciation deductions for non-residential buildings did not feature prominently in its policy announcement. However, with this proposal now forming part of both major parties’ tax policy for this election, it is likely that depreciation on commercial property will be “switched-off”, unless keeping depreciation for commercial buildings is a bottom line in any coalition negotiations. This proposal could have significant ramifications for many taxpayers. In addition to the tax impact (loss of deductions), there are practical implications such as reporting requirements in relation to deferred tax which, based on our experience from when building depreciation was removed in 2010, will need to be carefully worked through. The frequent changes to these policy settings (and resulting uncertainty) could have detrimental impacts on investment decisions as well as creating unnecessary compliance costs. We also note that depreciation for non-residential buildings was not brought in as a temporary Covid-19 business support measure (as has been characterised by the Labour Party). Rather, it was a recommendation of the 2018 Tax Working Group which the Government brought forward as part of its Covid-19 business support package.

Finally, although Government spending decisions are not strictly tax policy decisions, we do note that the National Party’s proposed spending cuts include cuts to funding for Inland Revenue’s budget. Any funding decisions regarding Inland Revenue should involve careful consideration of the impact on the tax system as a whole and Inland Revenue’s ability to administer tax and social policy and make appropriate compliance/enforcement interventions.

GST

The Labour Party recently announced what appears to be its main tax policy proposal ahead of the upcoming general election - removing GST from fresh fruit and vegetables.

However, just as important as the announcement on GST are the various statements made by the Prime Minister in relation to what the Labour Party will not campaign on in this election. In July, the Government proactively released a number of documents which outlined detailed policy advice received in the lead-up to the 2023 Budget. Treasury and Inland Revenue officials had been asked to design and cost a “tax switch” whereby personal tax relief would be provided (a tax-free threshold of $10,000, tax bracket adjustments, and increases to benefits) in combination with any one of the following:

A wealth tax (1.5% on net wealth of more than $5 million)

A “minimum tax” on high-wealth New Zealanders based on their “deemed income” as a percentage of their net worth; and/or

A tax on “supernormal profits” derived by large banks.

The Government also received advice in relation to imposing a one-off flood levy to help fund New Zealand’s recovery from the adverse weather events earlier this year.

Ultimately, the Government decided not to proceed with the above measures and shortly after the public release of the documents, the Prime Minister ruled them out from being included as Labour Party policy in the upcoming election. The Prime Minister cited a desire to provide “certainty and continuity”, saying “Under a government I lead there will be no wealth or capital gains tax after the election. End of story.” The Minister of Revenue (Hon David Parker) subsequently resigned from the Revenue portfolio, admitting that he was “disappointed” by the Prime Minister’s decision and that it would be “untenable” to remain in the portfolio.

Against this backdrop, the Prime Minister announced that the Labour Party will “remove GST from fresh fruit and vegetables”. The Labour Party’s fact sheet on the proposal indicates that this policy is targeted towards relieving cost of living pressures as well as incentivising healthier food choices.

The policy proposes to treat the supply of “fresh” fruit and vegetables as zero-rated for GST purposes. This means that suppliers can still claim GST deductions in relation to their costs. The fact sheet does not specify whether zero-rating should apply throughout the supply chain (e.g. from the growers to wholesalers to retailers, etc.) or if it would only apply to retailers.

The fact sheet specifies that the scheme excludes “processed” goods, described as meaning “cooked or combined with other ingredients” (for example, canned fruit or vegetables would be excluded). However, “processed” would not include being “cut up and wrapped without additives” (so fresh bagged spinach would be zero-rated).

The Labour Party estimates that households will save around $20 a month on average as a result of the policy, at a fiscal cost of approximately $2.2 billion over the next four years.

In addition to Labour’s recent announcement, a number of other parties have published their intentions to tweak the application of GST to help address the cost of living concerns among voters. The broadest approach comes from TPM with a policy to remove GST from all food, followed by New Zealand First’s scheme to remove GST from “basic foods” including fresh food, vegetables, meat, dairy, and fish.

Finally, the National Party has promised to repeal the recently enacted GST rules which will apply to platform operators in the gig and sharing economy from 1 April 2024.

Overseas experience

Many other jurisdictions have zero-rated essential food items, including Australia, Canada, UK and Ireland. However, the zero-rating provisions are usually much broader than this proposal. Instead of just applying to fruit and vegetables, all contain territory-specific nuances. The numerous cases considered in overseas courts speak to the complexity of introducing zero-rating on food items. Whilst we can look to other territories to identify potentially contentious areas, we expect there will be numerous boundary issues arising from this proposal. These will all need to be considered on their own merit and, according to the specific drafting and design of the rule if implemented in New Zealand. Examples from other jurisdictions:

Boundary items such as puréed fruits or smoothies - a case in the UK considered that a smoothie was a beverage and not a liquefied fruit salad (Innocent Limited v HM Revenue and Customs [2010] UKFTT 516 (TC) (UK)).

Bundled items such as a bag of salad sold with a packet of dressing or food boxes - a case considered cold dip (which would be zero-rated if sold separately) was ancillary to the principal standard-rated supply of hot take-away food.

Another case concluded that a chocolate lolly kit should be zero-rated as food, despite the kits including plastic moulds and sticks.

PwC view

New Zealand’s GST system is widely recognised globally as being among the “best in class”. There are relatively few exemptions, it covers a broad base, and it collects a significant amount of revenue (around 25% of the tax take) at a relatively low rate (our 15% rate being below the OECD average). Therefore to date, New Zealand’s GST system has had far fewer boundary issues.

The Labour Party’s fact sheet states that by limiting the proposal to “fresh” fruit and vegetables, it is relatively narrow in scope so as to minimise potential boundary issues. However, any boundary gives rise to complexity and greater compliance and administration costs for taxpayers and Inland Revenue. For example, the fact sheet suggests that frozen vegetables should be zero-rated, whereas “processed” foods are excluded. “Processing in this context means cooked or combined with other ingredients”. However, frozen vegetables are often harvested, rinsed, blanched and then sliced before being frozen and packed. Should the blanching process take frozen peas out of the zero-rating rules? Businesses would then need to build new systems to identify and track zero-rated supplies of “fresh” fruit and vegetables, and apply the correct GST treatment. These are the kinds of issues which businesses and advisors would need to grapple with, which in our view adds unnecessary complexity,and question whether it is in the best interests of “New Zealand Inc.”

The objective of this proposal is to make fruit and vegetables more affordable, and to assist low and middle income New Zealanders struggling with cost of living pressures. However, there is economic research (e.g. advice provided to the 2018 Tax Working Group) which suggests that the GST system is an inefficient mechanism for achieving this objective. Inland Revenue and the Treasury have previously looked at the potential fiscal cost and benefits to individuals from removing all food and drink from the GST base (a wider exception than the Labour Party’s proposal). Officials found that in absolute terms, the wealthiest New Zealanders would receive three times the benefit of the poorest New Zealanders (approximately $53 vs. $14 per week in savings). For the same fiscal cost of removing GST from food and drink, it was concluded that direct cash transfers or income tax changes are likely to provide a greater benefit and can be more effectively targeted towards lower income New Zealanders. Alternatively, we are seeing other countries use technology to design a more progressive VAT/GST system. For example, to target the affordability of food for the end consumer, Uzbekistan introduced VAT credits on essential supplies for low-income citizens, delivered through an app, to enable targeted VAT cuts or exemptions.

Currently, there is limited information on how the price savings would be enforced. Research is inconclusive as to whether the full GST amount would be passed on to consumers. The fact sheet’s response to this is that the Grocery Commissioner will be tasked with monitoring whether the cost reduction will actually be passed through to consumers, but there is little other detail on how the Grocery Commissioner would enforce it.

Although the stated objectives of the policy may be worthwhile, in our view, the GST system should be used for the purpose it was designed - to raise sufficient revenue to fund the government’s goals. A concern would be the “slippery-slope” effect of potentially having more exceptions further eroding the broad-based approach we currently have in relation to our GST system, since its inception in 1985. In our view, there are better means outside of removing GST on goods to achieve the objective of easing the cost of living pressures faced by New Zealanders, including considering more direct ways of providing support.

Individual Taxes

Any changes to individual taxes will have a direct impact on every voter, so it is not surprising that most of the political parties have announced changes as part of their election policies, particularly given the focus on cost of living pressures.

The Green Party of Aotearoa New Zealand (Green Party), Te Pāti Māori (TPM), The Opportunities Party (TOP), and the New Conservatives have all announced tax-free thresholds for personal income tax. This is similar to Australia's approach where no tax is paid on the first $18,200 earned in a year. National, New Zealand First, and the New Conservatives have all suggested providing New Zealanders with tax relief by adjusting the existing tax brackets for inflation, and Act, the Green Party, TPM, and TOP have all published their proposed revised tax thresholds.

Going forward, the National Party has committed to assessing the impact of inflation on average tax rates every three years, with a view to making adjustments that are “affordable and responsible in light of the economic and fiscal conditions at the time.”

Below we have summarised the parties’ proposed revised thresholds:

Note: TOP’s “Fair Tax System” policy is broken into two phases. The second phase is proposed to apply from 2026 whereby a single income tax rate of 35% would apply to individual income excluding an annual universal basic income of $16,500 to residents aged between 18 and 65.

The parties have also suggested revisions to individual tax credit schemes as follows:

Labour and National have both proposed increasing the in-work tax credit from 72.50 per week to 97.50 per week.

National have proposed a number of other changes to individual and family tax credit schemes as follows:

Increasing the eligibility threshold for the Independent Earner Tax Credit (IETC) from $48,000 to $70,000.

Introducing a 25% tax rebate for childcare costs (up to a maximum of $75 per week) for families earning below $180,000. This is proposed to be administered by Inland Revenue and paid directly to individuals/families based on attendance data collected from early childhood education providers.

Act suggests the introduction of a “Low and Middle Income Tax Offset” to the amount of $800 per annum for those earning between $12,000 and $48,000.

The Green Party’s policy includes replacing the Working For Families scheme with weekly child caregiver payments of up to $215 per week for one child, and an additional $135 for each additional child. This policy is a part of the Green Party’s broader Income Guarantee policy under which everyone in or out of work would receive a weekly income of at least $385 per week for an individual, $770 for a couple, or $735 for a single parent.

TOP has announced a scheme to extend the existing In-Work Child Tax Credit to all children of low-income families, and to remove all Ministry of Social Development debt.

The New Conservative party’s FamilyBuilding tax policy intends to (i) allow couples with children to divide income between parents to receive a tax benefit, and (ii) replace the Family Tax Credit and In-Work Tax Credit schemes with a simplified $2,500 child tax credit available individually to two parents up to a maximum of $5,000 per child.

PwC view

Purely from a tax policy perspective, there is a compelling rationale for some adjustments to the current personal income tax rates, particularly given the impact of fiscal drag in the current inflationary environment. Fiscal drag (or “bracket creep”) refers to the concept that a person may be pushed into a higher tax bracket purely due to the impact of inflation.

The current personal income tax rates have been unchanged since 2010. According to the Reserve Bank’s inflation calculator, general inflation over that period has increased prices by around 37% (i.e. something that cost $100 in 2010 would cost roughly $137 today). According to the Treasury, a person earning $48,000 in 2010 would now be earning $61,427, pushing them into the 30% tax bracket and increasing the amount of income tax that person pays, although in “real” terms they are no better off than they were in 2010. Someone on today’s minimum wage working full time is likely to be close to the $48,001 threshold, where the 30% rate kicks in. The following diagram from the Treasury illustrates the impact of fiscal drag on the distribution of taxpayers across the marginal tax rates:

Figure 1: Proportion of taxpayers in each bracket

Source: “Initial Advice on Personal Tax Relief”, Inland Revenue and the Treasury (10 February 2023)

The Treasury considers that having a higher proportion of earners with higher marginal tax rates could lead to lower incentives to work and save over time.

From a tax policy perspective, the 2018 Tax Working Group recommended against introducing a tax-free threshold and this position was reiterated by the Treasury and Inland Revenue in recent advice provided to the Government as part of the 2023 Budget. Tax-free thresholds (such as those proposed by the Green Party, TPM, and TOP) are unlikely to be a cost effective way of addressing distributional objectives, because everyone (from the lowest to the highest earners) will receive a benefit. They also tend to be very expensive - the Treasury forecast the cost of a $10,000 tax-free threshold to be c. $13.8 billion over a four-year period. Rather, more targeted transfer payments (e.g. increases to benefits or the Working For Families tax credit) or bracket adjustments are likely to be more cost-effective ways of achieving such distributional objectives.

The administrative impacts of the proposals will need to be carefully worked through. For example, the National Party’s proposed bracket adjustments would apply from 1 July 2024, and there may be complexities associated with changes to personal tax rates part-way through a tax year. The proposed FamilyBoost policy may also require systems changes and greater compliance and administrative costs to collect and process attendance data from early childhood education providers.

In addition to personal income tax brackets and rates, it is important also to consider the role of the transfer system, in particular the Working For Families tax credit, and the interaction between the two. The impact of a tax-free threshold on the current income abatement thresholds for social policy entitlements will need to be considered by any party proposing a tax-free threshold. For example, the Green Party proposes to replace Working For Families entirely with its Income Guarantee policy.

Overall, it is important to consider any changes against the overall system and how it interacts together to ensure there are no unintended consequences.

Corporate and Trust Taxes

While most parties' tax policies are centred around individual taxation and how it can be adjusted to ease cost of living concerns, the Green party, TPM, and TOP have all published policies with a corporate and trust tax lens.

The Green Party and TPM have each proposed increasing the corporate tax rate to 33%, returning to what it was in income years from 1996/1997 to 2007/2008.

The Green Party’s tax policy also includes the introduction of a 1.5% tax on assets held in private trusts. Trusts with a “beneficial social purpose will be exempt”, including Māori land trusts, Treaty of Waitangi post-settlement trusts, charitable trusts, or disabled beneficiary trusts.

Phase 2 of TOP’s tax policy includes a move to a single income tax rate of 35%, which would also apply to company and trust income.

The current Labour Government has already proposed an increase to the trustee tax rate to 39%, to align with the top marginal personal tax rate. This was included in an omnibus taxation bill introduced on Budget Day 2023, and could be brought back to be enacted after the election, depending on who forms the next Government. Details on this proposal can be found in our May 2023 Tax Tips.

PwC view

From a tax policy perspective, there is some appeal to more closely align the corporate tax rate, trustee tax rate and top personal tax rate. Misalignment of tax rates applying to different business structures could give rise to distortions in commercial decision-making (i.e. influencing choice of business structures purely for tax reasons). However, the pursuit of rate alignment should not be absolute, and careful considerations should be given to ensure there are no unintended consequences. No party is proposing to remove or reduce the top personal tax rate of 39% in the near term.

However, any changes to corporate tax rates need to consider the impact on foreign investment and productivity. The 2018 Tax Working Group concluded that New Zealand’s imputation credit regime means that the corporate tax rate is largely a withholding tax for domestic investors but acts as a final tax on non-resident investors. Research suggests that the corporate tax rate may be a more significant factor in investment decisions when choosing between two countries which are close substitutes (e.g. New Zealand and Australia). New Zealand’s current corporate tax rate is already above the OECD average but crucially, increasing our corporate tax rate to 33 or 35% would put ours above Australia’s headline rate of 30%.

Research from Inland Revenue’s Long Term Insights Briefing suggests that the relationship between corporate tax rates and foreign investment / productivity is complex. In our view, a more detailed evaluation of New Zealand’s overall tax settings and rates is required to ensure that we fully understand the impact any changes may have that stems beyond the direct revenue from corporations.

Wealth Taxes

The Prime Minister has ruled out introducing any wealth taxes or capital gains taxes under his leadership if elected into Government. Only two parties, the Green Party and TPM, have announced an intention to introduce wealth taxes.

The Green Party’s policy is to introduce a 2.5% tax on net assets over $2 million for an individual or $4 million for a couple. The tax would apply on the net value, excluding mortgages and other debts, and payment could be deferred until sale of the asset. Valuation of high value property would be based on insured value, and everyday household goods including vehicles worth less than $50,000 would be excluded to simplify application. Māori land under the Te Ture Whenua Māori Act would be exempt and so would the assets of Post-Settlement Governance Entities, such as land returned under a Treaty Settlement or vested in a Treaty Settlement Entity. The assets of charities, NGOs, clubs, and other entities would also not be part of anyone’s individual taxable wealth.

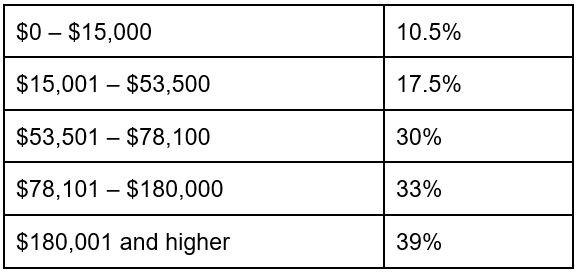

TPM’s policy is to introduce a bracketed wealth tax system. This would be broken down as indicated on the table to the right. The rates would apply to assets less debts owing, calculated on an individual basis or the combined net wealth of couples. The tax would be payable annually and capture accrued capital gains.

PwC view

The 2018 Tax Working Group recommended against wealth taxes or land value taxes (and instead favoured a realisation-based capital gains tax).

Wealth taxes are difficult to design and enforce, in large part due to the need to value assets and liabilities annually. Some assets (e.g. privately held companies or start-ups) are particularly difficult to value objectively. From an economic perspective, the Treasury’s advice to the Government indicated that a wealth tax could have a negative impact on incentives to save and invest, due to the impact of a wealth tax on the after-tax returns on investment required to make it worthwhile. For example, an investment which may have previously presented a 2% return might no longer be viable if a 2.5% wealth tax applied each year.

There is also research which suggests that wealth taxes could result in wealthy New Zealanders leaving the country. This not only reduces the tax base, but the economic activity created by these individuals and their enterprises could also leave the New Zealand tax base. The Treasury estimated that for every 1% of the rate of a wealth tax, around 5% of those who are subject to the wealth tax could leave the country.

For these reasons, the general trend internationally has been a shift away from wealth taxes. Many will recall that capital gains tax has been the subject of many discussions in previous elections. As such, it may be that political parties which are motivated towards increasing the progressivity of the tax system see a wealth tax as being more palatable. However, in our view, we still consider that from a tax policy perspective, a realisation-based capital gains tax with a recycling of revenue in lower personal taxes would be preferable to a wealth tax.

Property Taxes

The parties have very split approaches to property taxes, with Labour, National and Act revising recent rule changes, whereas TPM and TOP intend to introduce new property taxes.

Labour has announced that it intends to remove the re-introduced depreciation for non-residential buildings - in part to fund the proposal to remove GST from fresh fruit and vegetables.

National has announced three property tax commitments - (i) unwinding the 10 year bright-line extension and bringing the brightline period back to two years (with effect from July 2024, for properties acquired before July 2022), (ii) re-introducing interest deductibility for residential rentals, (iii) rejecting the proposed light rail levy on houses along the Auckland light rail system. National’s proposed reinstatement of interest deductibility is proposed to be phased back in as follows:

April 2024: 50% deductible

April 2025: 75% deductible

April 2026: 100% deductible

Act has taken a slightly stronger but similar position, intending to (i) abolish the bright-line test and (ii) re-introduce interest deductibility for residential landlords.

TPM’s property tax initiatives include (i) an Undeveloped Land Tax at 33% of the increased value of undeveloped land at 4 years after purchase, calculated as the current market value of the land less the original purchase price of the land, (ii) a Vacant House Tax at 33% of the market value payable on all properties that do not have a tenant after a 6-month period, calculated as the current market value of the property including land and buildings less the purchase price.

TOP has announced an intention to implement a 0.75% land value tax on urban residential land paid annually, with an increase to 1.25% in Phase 2 of their tax policy.

PwC view

The recent reforms to the taxation of real property have resulted in a complex system of rules which has significantly eroded the coherence of the tax system. In particular, the interest limitation rules are difficult to reconcile against the broad-base, low-rate tax policy framework which has informed New Zealand tax policy design for over 30 years (across both National and Labour led governments). In our view, a principled and coherent tax system should treat different classes of investments equally so as not to distort investment decisions. The Government may argue that the interest limitation rules have achieved their policy intent, given the recent fall in house prices. However, it is difficult to single out the impact of any single policy on the housing market more generally - and wider economic conditions such as interest rates cannot be ignored when considering the housing market.

As discussed above, both major parties have committed to remove depreciation deductions for commercial buildings. While this has been described by some as removing a “tax break”, advice provided by the Treasury and Inland Revenue to the 2018 Tax Working Group found evidence that buildings do in fact depreciate. As such, depreciation deductions to reflect the true economic life of buildings is intended to minimise distortions to investment decisions.

Many economists argue that a land value tax is an efficient one on the basis that it is almost impossible to avoid (as land is immovable) and it incentivises more efficient and productive uses of land. However, the 2018 Tax Working Group ultimately recommended against land taxes on the grounds of horizontal equity. A land tax only impacts one type of asset, which could have a disproportionate effect on certain groups and industries - for example, farmers. There are also complex issues relating to Māori land (including Treaty of Waitangi considerations) which would need to be worked through. Māori stakeholders have already voiced strong opposition to a land tax in submissions to the Tax Working Group.

Environmental taxes

- There has been significant movement in environmentally oriented taxes in recent years as climate concerns have become more and more prominent for voters.

- National has indicated that they wish to unwind the clean car scheme that currently applies in relation to the importation of CO2 emitting vehicles.

- National and the New Conservative Party are aligned in their policy to remove the regional fuel tax.

- Labour has announced incremental increases to fuel excise duty to a total of 12 cents per litre over 3 years, whereas National have promised no increases to fuel excises in its first term.

- Act has published a revised plan for the Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS). Under the Act scheme, ETS auction revenue would be refunded to taxpayers by dividing total revenue by the population of New Zealand and crediting each New Zealand adult’s tax bill by that amount, plus their dependent children’s share. The National Party have also referred to an “ETS dividend” as part of their tax policy. However, unlike the Act party proposal, the National Party proposes to use ETS auction revenue to fund its general tax relief package, rather than a pure recycling of ETS revenue each year.

- The Green Party has announced that it proposes to allow a tax deduction for “zero-carbon upgrades” for rental properties (for example, installing solar panels).

- Labour recently announced that the road user charge exemption for electric vehicles will end.

Conclusion

As always, we expect tax policy discussions to feature prominently in this year’s election campaign. In a free and democratic society, it is ultimately up to voters and the politicians they elect to determine the policy objectives of the government of the day. Until recently, there has been broad consensus that the tax system should be used to efficiently raise revenue to support those policy objectives. However, based on the various tax policies announced, we are seeing a trend towards using the tax system to directly affect other policy objectives.

In our view, the broad-base low-rate tax framework has served New Zealand well and we continue to support a cohesive, principled approach to tax policy development going forward, but recognise that in some instances, it may make sense to pull the tax lever to encourage certain behavioural change. However, careful consideration should be given before this is done to ensure there are no unintended consequences.