In recent years, infrastructure has been a key concern for New Zealanders, reflecting historical delays, indecision and a lack of long-term planning. The coalition Government has highlighted its focus on infrastructure by outlining a 30-Year National Infrastructure Plan, due to be delivered by December 2025, and plans to loosen restrictions on foreign investment by amending the Overseas Investment Act. New Zealand First is also advocating with its coalition partners for a $100b "Future Fund" dedicated to long-term infrastructure projects.

While investment is a priority, tax considerations have not yet come to the forefront of the conversation. In this Tax Tips we examine the New Zealand tax settings in relation to infrastructure projects and consider the role that tax may play.

Current tax settings for infrastructure projects

The characteristics of infrastructure investment are relatively unique. These are large scale, expensive projects which can take years to come to fruition. As a result, they have particular tax features and sensitivities.

Given the long-term nature of these projects, ensuring certainty of tax treatment is essential as it feeds into the financial modelling of investors

The high capital expenditure involved in these projects raises questions around deductibility of that expenditure and the timing of any tax deductions

Risks around black-hole expenditure are more pronounced, again due to the size and scale of pre-commencement spending

As these projects typically involve high debt-funding, interest deductibility rules around transfer pricing and thin capitalisation are more acute

The tax profile of counterparties, which may include Government or tax-exempt entities, can add another layer of complexity

Tax loss retention is a valuable consideration, but has become less of an issue with the introduction of the business continuity test for companies

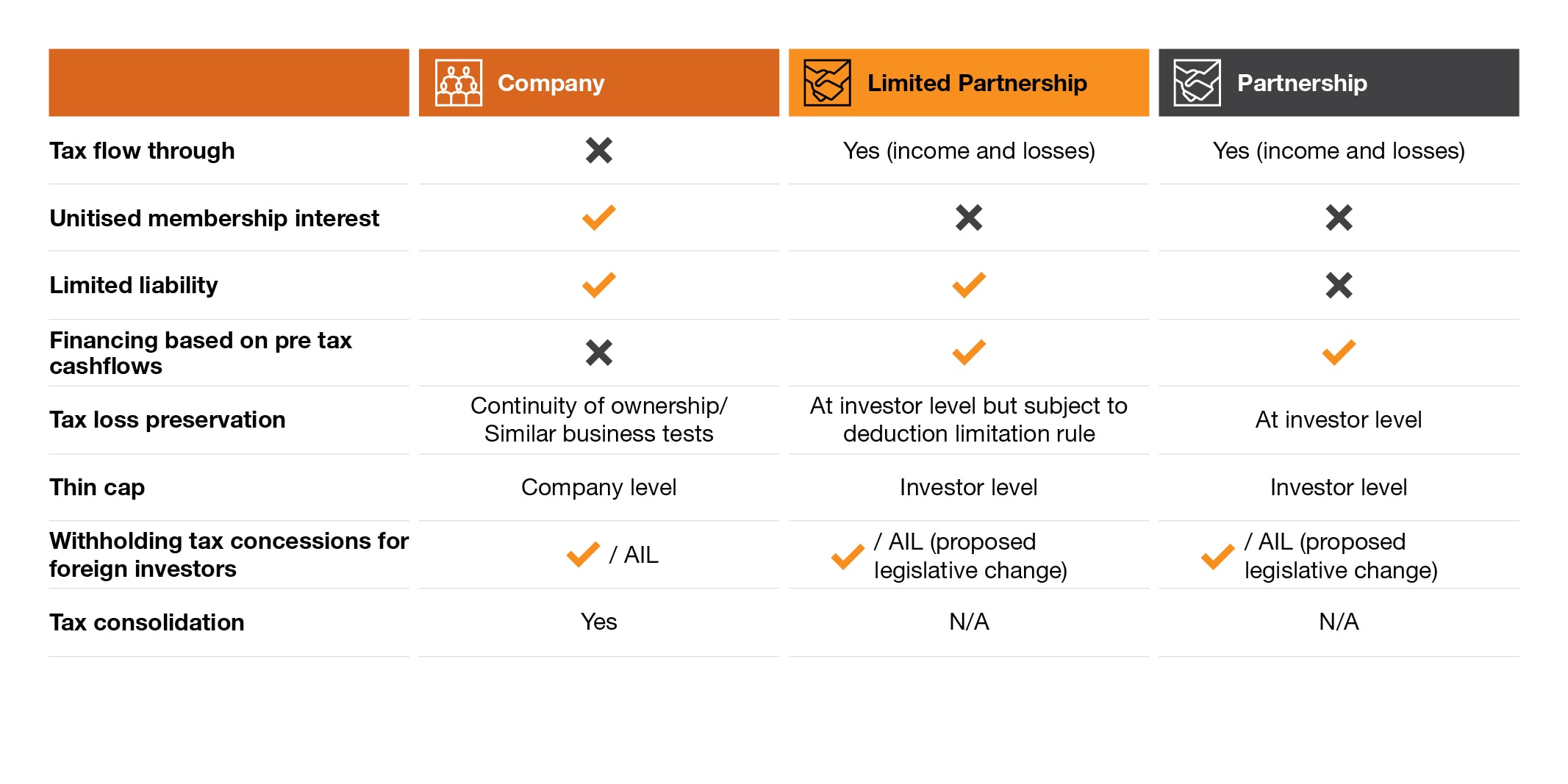

The choice of legal structure to undertake a project will impact the tax profile. We outline the key tax and commercial implications of using either a company, limited partnership (LP) or general partnership structure.

There are a number of differences that can arise based on the type of legal structure used. Ultimately, there will always be trade-offs between the choice of vehicle. For example, general partnerships may not be suitable for commercial reasons due to their unlimited liability.

In New Zealand, we would typically see the use of either a company or a LP as the vehicle choice for undertaking infrastructure projects. The decision between a company and an LP involves trade-offs and depends on several factors, including the importance of flow-through tax treatment (which is particularly relevant if there are different tax profiles among investors), the mix of foreign and local investors (e.g. thin capitalisation consideration) and the appetite to navigate tax complexity (LPs typically have more complexity).

Finally, it is worth noting that there are minimal specific tax rules that apply to infrastructure projects in New Zealand, with the main one being an exception to the thin capitalisation rules for certain public infrastructure projects.

Infrastructure tax levers worldwide

Unlike New Zealand, a number of countries have specific tax rules that apply to infrastructure projects. We provide a high level summary of some of these below.

Australia offers a designated infrastructure project tax loss incentive, which reduces the risk of forfeiting losses or not being able to utilise them for extended periods. Additionally, Australia provides investment tax credits for certain types of projects, accelerated deductions for capital expenditures, and an approved economic infrastructure tax concession that is relevant for the managed investment trusts (MIT) regime.

In Canada, a 10% federal income tax credit is available in specific regions for various forms of capital investment. This generally applies to new buildings, machinery and equipment, and clean energy generation equipment used primarily in manufacturing, processing, logging, farming, or fishing. Canada has also recently passed into law new refundable investment tax credits for the development of clean technologies (20-30% of capital cost), clean hydrogen production (15-40% depending on carbon intensity), clean technology manufacturing (30% of investments in certain depreciable property), and clean electricity generation (15% of eligible investments).

China offers tax incentives for key public infrastructure projects and projects engaged in environmental protection. These projects are exempt from tax for the first three years and taxed on 50% of income for the following three years.

Ireland, similar to New Zealand, has interest limitation rules aimed at limiting base erosion using excessive interest deductions. The rules limit the maximum net interest deduction to 30% of Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation, Amortization (EBITDA). Ireland has an exception to these rules for long-term public infrastructure projects, which include projects to provide, upgrade, operate, or maintain large-scale assets in the general public interest. Finland shares a similar interest limitation exception.

The United States (US) introduced several federal tax credits under the Inflation Reduction Act 2022, including credits for zero-emission nuclear power plants, clean electricity production, and clean fuel production. The US also provides tax credits for infrastructure investments such as manufacturing facilities, the renewable electricity production credit, the railroad track maintenance credit, and an exemption for qualified foreign pension funds from capital gains tax and withholding tax on distributions.

Should New Zealand introduce a preferential tax regime for infrastructure investments?

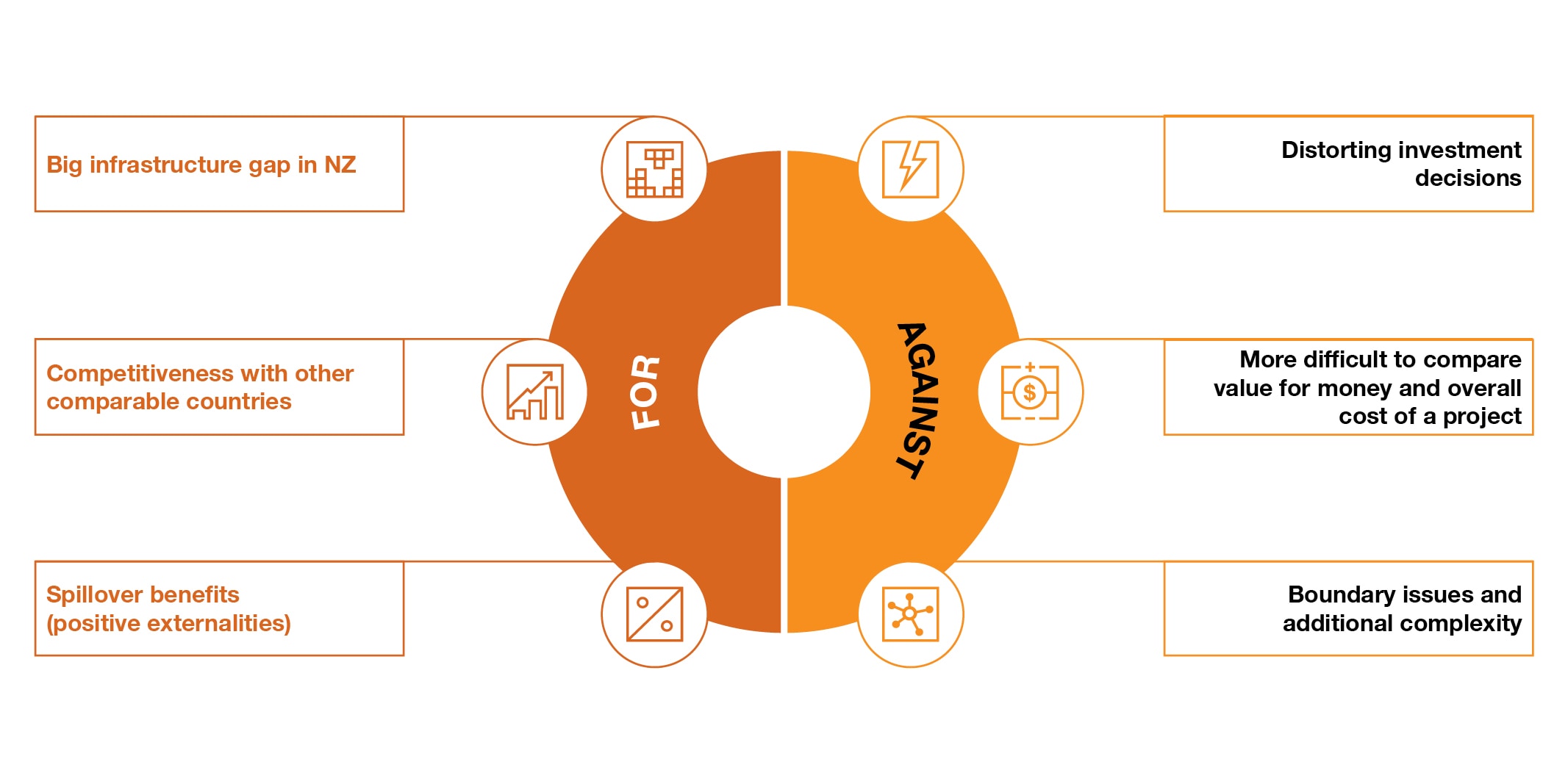

This issue was considered by the Tax Working Group (TWG) in 2018. TWG weighed up the pros and cons of introducing preferential tax treatment for infrastructure projects and outlined its thinking in a discussion paper.

The key proposals considered by TWG were:

Applying a lower tax rate than the corporate tax rate to qualifying projects for a meaningful part of the life of the asset;

Eliminating further tax on profit distributions to foreign and domestic investors; and

Allowing full deductibility of third-party non-recourse funding.

The proposals were largely built around implementing a Nationally Significant Infrastructure Project (NSIP) regime, similar to what Australia had announced earlier that year. Australia introduced an approved economic infrastructure tax concession in relation to its MIT regime whereby a reduced 15% tax rate was available to Government approved NSIPs for 15 years. However, as pointed out by the TWG, the resulting concession was introduced to tighten the rules around foreign investment in Australia generally. To implement such a regime would actually loosen the rules for New Zealand.

The pros and cons of pulling the tax lever

TWG’s analysis noted the direct benefits of introducing a preferential regime - incentivising tax sensitive investment towards infrastructure projects in New Zealand’s interest, and with that importing the knowledge and experience of investors who have managed such investments in the past. However they also outlined a number of detractors, including drawing resources away from other industries, issues around principles of fairness, and distortions to the Government’s value-for-money decision making in prioritising spending.

The TWG also noted that the Treasury’s public-private partnerships team reportedly did not experience issues with attracting interest from overseas or domestic equity investors, and so found it unnecessary to incentivise them by way of concessions.

PwC view

New Zealand has historically applied a broad-based low rate (BBLR) framework to assess tax policy. A key feature of this approach has been to limit the use of tax incentives to achieve a particular outcome. While this has largely been a successful way of efficiently raising tax revenue for the Government of the day, the New Zealand tax system is not without its departures from the BBLR framework.

In that context, it is worthwhile considering whether tax incentives could play a role in encouraging infrastructure investment in New Zealand, particularly when the infrastructure gap is so large that it requires additional help to correct the gap (e.g. correct a market failure). Care will need to be taken to ensure that any change is well targeted and there is value-for-money for New Zealand.

Consideration should be given to ensure there are no unintended barriers in our tax rules that make investing in New Zealand infrastructure projects less attractive. An example is the limited partnership tax regime and whether compliance complexity can be reduced to make the use of such structures more efficient.

Finally, as reflected by the Government’s recent policy proposals, although it is an important consideration, tax is not the only (or even the most impactful) regulatory setting that impacts New Zealand’s ability to plan and deliver infrastructure projects. Tax is just one of many levers available to the Government to encourage infrastructure investment into New Zealand.