A guide to Doing Business in Aotearoa New Zealand

Kia ora,

As we look ahead, it's evident that change remains the sole constant, both in Aotearoa New Zealand and across the globe. We work with our clients to navigate the evolving landscape, enabling you to achieve outcomes that benefit your business, the economy, and our communities.

This guide brings together our extensive knowledge and experience of doing business in New Zealand, drawing on expertise from across our firm. In it, you’ll find an overview of our distinctive economic, social, and regulatory environment; detailing the business structures, capital markets, mergers and acquisitions, overseas investment regulations, taxation, and other essential laws and regulations to consider when planning to invest or do business here.

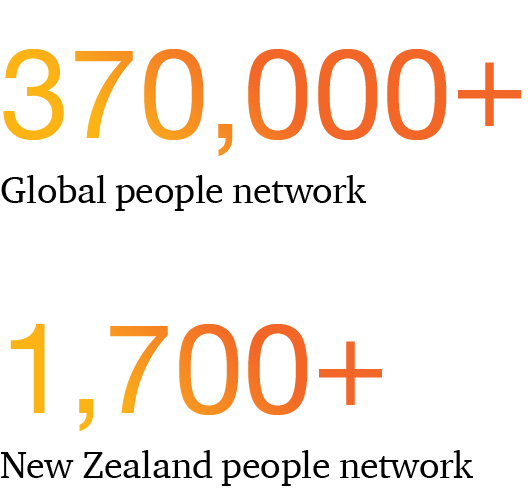

If you need further information please reach out to our team. With our extensive range of services and global network of specialists, we aim to make your entry into or expansion within New Zealand seamless and straightforward.

Doing Business in New Zealand Aotearoa New Zealand as an investment opportunity

Aotearoa New Zealand presents a compelling investment landscape, enhanced by a robust network of trade partnerships across Asia, the Pacific, the Americas and the European Union. It advocates for free trade, and the removal of unfair competitive practices and trade-distorting subsidies.

New Zealand’s stable democratic political system, strong legal institutions, and resilient economy make it a highly desirable destination for overseas investment. Its transparent and open-market economy, along with a free-floating currency, presents significant opportunities. Internationally, New Zealand is frequently recognised for its business-friendly environment, ranking 11th on the Index of Economic Freedom in 2025 and 4th among the least corrupt countries in the world, alongside Denmark, Finland, and Singapore, in Transparency International’s 2024 Corruption Perceptions Index.

The New Zealand Government welcomes sustainable, productive and inclusive overseas investment and recognises its contribution to the overall prosperity of the country. While some foreign investments require regulatory approval under the overseas investment regime, not all transactions do; the necessity for consent is determined by the nature and value of the investment. Currently, as part of its 'open for business' initiative, the Government is reviewing pathways for high net worth migrants and has created Invest NZ, a dedicated agency to engage with international investors. Additionally, New Zealand is preparing for significant reforms to its overseas investment framework, with major changes expected in the coming year.

Government and the legal system

New Zealand is an independent nation and its Government is modelled on the Westminster system.

This system is based on separation of powers, a concept intended to prevent abuses of power within Government, with each branch acting as a check on the others. The Government is led by the Prime Minister and consists of three branches: Parliament, Executive, and Judiciary.

Laws are written by the Executive and are passed through Parliament. Parliament is elected by the public through a democratic election every three years.1 It determines which laws to pass by examining and debating proposed laws, also known as bills. The Executive is made up of the Prime Minister and the Cabinet Ministers, who administer the law. Some of their powers and obligations are delegated to local councils and tribunals. The Judiciary interprets and applies the law by hearing and deciding cases, and keeps the balance between the power of the Government and the rights and responsibilities of New Zealanders.

Business landscape

New Zealand’s rich natural resources have afforded the country significant resilience against economic disruption. New Zealand’s primary sector remains integral to the economy and has remained financially robust, despite the considerable impact of severe weather events, the availability of labour, and supply chain challenges.

Unlike most OECD developed economies, New Zealand has a remarkable reliance on the food and fibre sector as a significant contributor to its prosperity. Food and fibre sector export revenue is expected to increase to $59.9 billion for the year to 30 June 2025, representing the country’s largest contribution to the tradable economy.2

Leveraging New Zealand’s comparative natural advantages will ensure the country continues making world-leading strides forward in the food and fibre sector. While quality products will always be in demand, New Zealand has the opportunity to strategically position its food and fibre sector to offer high skills, knowledge, technology, and capability to countries with the existing resources for production. Much of New Zealand’s success in the food and fibre sector can be attributed to its capability in processes, systems, and technology, turning sunlight and nutrients into a broad range of products for consumers around the globe.

International trade

China, USA and Australia are New Zealand’s largest trading partners, with the European Union emerging as an increasingly important market for New Zealand. Taking advantage of its international reputation with a strong and growing network of international trading partners, New Zealand has successfully concluded a number of free trade agreements. In particular, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) have helped New Zealand to diversify and secure access across a broad range of Asian and Pacific markets.

Top exports by country

Top export products

Source: Stats NZ Tatauranga Aotearoa

Top imports by country

Top import products

1 The term of Parliament is being reviewed by the current Government, following the recommendation of an Independent Electoral Review.

2 Transforming New Zealand's Food and Fibre sector for global prosperity